Most of us have an idea about what constitutes a healthy diet. The advice from clinicians and scientists seems to be constant — we should all aim to eat more fruit and vegetables, and limit intakes of meat, alcohol, and sugar.

A person who eats well can expect to live longer and healthier than someone who doesn’t. Yet, apart from some added nutritional benefit, we have never really understood how healthy eating prolongs life. Until now.

In fact, scientists are coming to realize that a diet aimed at extending the human lifespan isn’t down to just what you eat, but when. But first, they had to understand why it is we age in the first place.

Understanding why we age

The most popular theory behind why we age is the information theory of aging. It puts the aging process down to a simple loss (or corruption of) information over time.

By ‘information’ we mean how our genes function in our body. Genes are like instructions that tell our body how to behave, but our genes can be ‘changed’ or ‘expressed’ in two different ways: genetically and epigenetically.

Genetic information is ‘stored’ digitally in the body, whereas epigenetic information is stored in the analog format. It is a bizarre concept, but think of it this way: analog vinyl used to be the records of choice to listen to music.

They sound great, but the quality quickly deteriorates after a while. Types of vinyl were eventually replaced with digital CDs, which might not sound quite as superior, but they last much longer, because digital is a more robust way of storing information.

The epigenome is like a CD player reader. Because analog information corrupts over time, the reader can no longer read our genetic information (the CD).

Activating our ‘longevity genes’

In the same research into the process of aging, scientists have identified seven genes that try to slow down this loss of information.

We call them longevity genes (actually, in the literature, they are referred to as sirtuins). These longevity genes are like emergency response units. They move from cell to cell, repairing DNA whenever it breaks or makes an error in mutation.

Unfortunately, our longevity genes cannot keep up the pace, because the errors soon mount up and cause the decline we associated with old age.

But scientists are finding new ways to help out our body’s emergency response workers. It actually turns out that our longevity genes are a bit lazy, and we can trick them into working harder by making the body think it’s in trouble.

Eating to trigger longevity genes

Our longevity genes work hard whenever the body appears to be in uncertain or troubling times. This can be when we exercise strenuously or are exposed to temperatures that are uncomfortably hot and cold and more.

One way to put our bodies under a form of mild stress is by obtaining all of our amino acids from plant-based materials only.

We can get all the necessary amino acids from plants (including lentils, almonds, chickpeas, etc.) — enough to be healthy and function well — but plants contain very little compared to meat. On the contrary, most omnivores probably consume far too many amino acids already.

By switching to a plant-based diet, we can amino-fast. The body sees a rapid reduction in the intake of amino acids.

This doesn’t do any harm, but it sends the alarm bells ringing for our longevity genes. As a result, our longevity genes respond by rushing out to our cells, and repairing our DNA as it breaks.

The ‘Rabbit Lunch’ — and why organic food is better for the body

In order to increase longevity, mild stress is a good thing. (Note the emphasis on ‘mild’ — serious stress is not good at all.) And this seems to be a universal trait in plants and animals.

For example, when fruits and vegetables are grown organically, they are subjected to more stressful conditions than their waitered-on pesticide-treated non-organic cousins.

The more stressful conditions force the release of a compound known as resveratrol, which once consumed by humans, becomes an agent that helps our longevity genes to work that bit harder.

Resveratrol is particularly concentrated in fruits, and in particular strawberries. But it is also abundant in red wine as well. One glass of red wine may have as much as 1 – 3mg of resveratrol alone.

So it seems an organic (if you can purchase organic) ‘Rabbit Lunch’ is the best diet to eat in order to promote longevity.

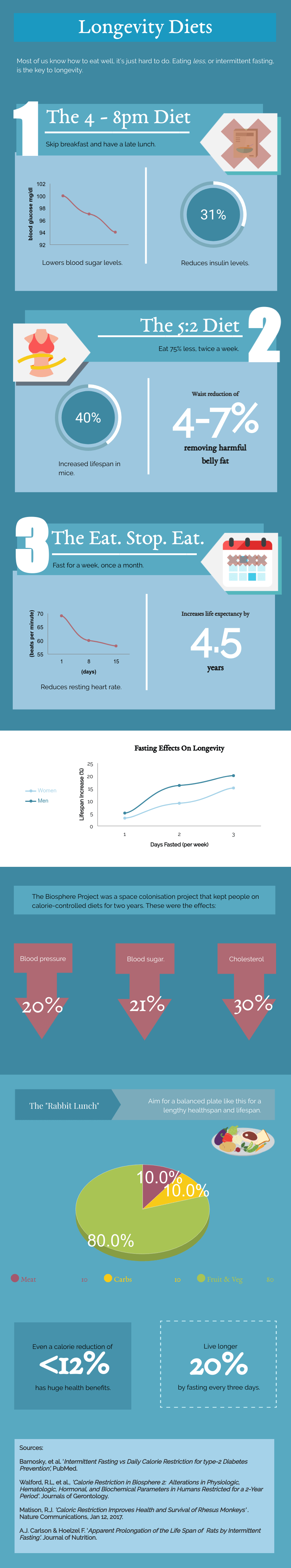

Actually the Rabbit Lunch isn’t strictly vegetarian, only predominantly so. It still allows for meat and carb foods, but these two should not take up more than 20 percent of the plate combined.

Of the vegetables, it is important to try to eat as many different colors as possible. The blue-purple fruits, in particular, have several compounds in them that are thought to have anti-cell ageing effects, including eggplants (aubergines), purple cabbage, and purple asparagus.

It’s not just what you eat, but when you eat

Amino-fasting and consuming resveratrol is important for anyone following a longevity diet, but they only represent a small part of the picture. Because a crucial determiner is when we eat our meals.

The ultimate form of mild stress, the one that really kicks our longevity genes into action, is hunger. Not starvation. No malnourishment. But the gentle twang of hunger, of living in a state of want for more food.

For almost all of human history (until about the 1950s), most people did not know where the next meal would come from — and they often went hungry.

The feeling of always being satiated is a new phenomenon, and it is not normal. At least in the overarching evolution of our species.

What that means is, whenever we go hungry, our longevity genes start to panic and kick into survival mode. They rush out and repair DNA as quickly as they can. That is the power of fasting.

Fasting to trigger longevity genes

Hundreds of studies have demonstrated the beneficial aspects of fasting, both in terms of mental and physical health. Fasting doesn’t have to be difficult or permanent, either.

It can even be more convenient for some peoples’ lifestyles. It also tends to be more affordable because it entails buying less food.

There are lots of diets that incorporate fasting, that work very well to stimulate our longevity genes. Here are three broad ones, of which at least one should appeal to most people:

- The 4 – 8 pm diet — This requires fasting in the morning by skipping breakfast (an easy feat for a lot of people) and then having a late lunch in the afternoon and an even later dinner.

- The 5:2 diet — Followers of this diet only need to fast for two days of the week, skipping out 75 percent of their calorie intake. This diet is especially good at removing harmful fat from around the waist and stomach.

- The Eat Stop Eat diet — This one requires one week of every month fasting on a sharply reduced calorie intake.

One of the most famous fasting experiments was indirect. It involved a group of pretend-astronauts sealed into a glass dome for two years while they attempted to grow their own food and obtain self-sufficiency.

The so-called Biosphere Project — carried out for space colonization research — was a failure, but after years of fasting, the astronauts emerged from the dome with drastically lowered blood pressure, sugar and cholesterol, heart rates, and more.

Lowering these risk factors reduces our chances of getting chronic and debilitating illnesses later on in life (which are sometimes referred to as age-related illnesses). But there’s more.

Studies of fasting have shown that mice can live up to 40 percent longer, and men and women anywhere between 5 – 20 percent longer. That’s the power of mild stress, from feeling mildly hungry from time to time, of giving our longevity genes a proverbial kick up the backside to improve DNA repairs and function.

Some thoughts and conclusions

Longevity dieting is all about tricking the body’s emergency repair forces into action. We all have longevity genes that are ‘lazy’. By making them work harder, we can expect to live longer, healthier lives. The key is mild stress for short, intermittent periods of time.

The best way to do this is to eat organic food subjected to mild stress itself and to miss a few meals every now and then. It is practical and affordable to do because it often entails a reduced food bill anyway.

Follow all of these steps, and you may increase your lifespan — as well as your healthspan — substantially.

About The Author:

Neil Wright is a writer and researcher. He has an interest in travel, science and the natural world, and has written extensively about longevity and health on his website.